Floyd wants to be unstable.

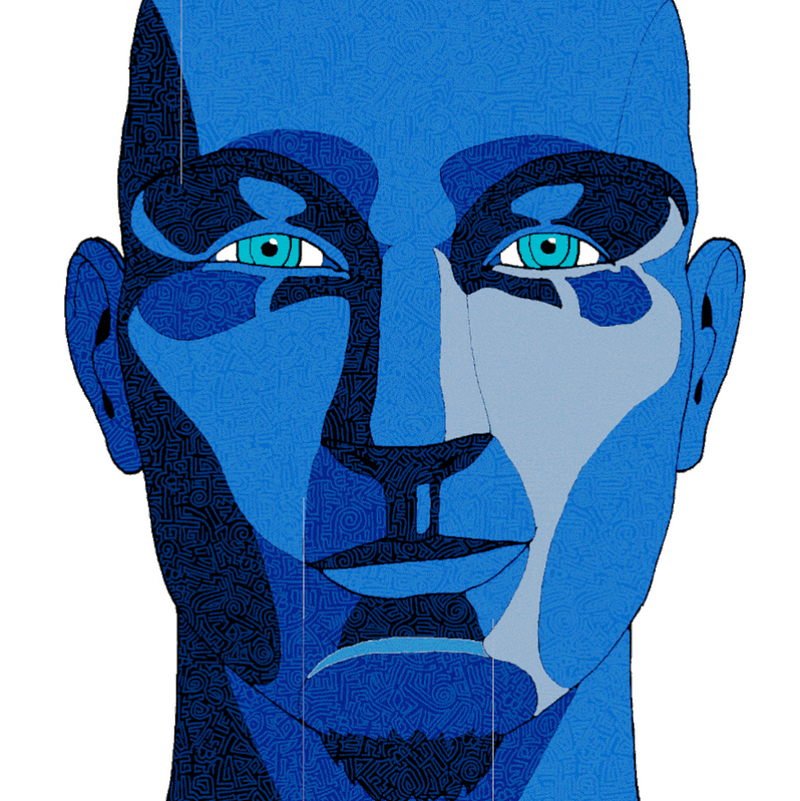

Don’t try finding consistency in Fabiello’s Floyd’s Facets, the Milanese artist’s first and only piece housed in MOCA’s permanent collection. Floyd is art in constant flux, ceaselessly shifting between placements and colors. Throughout the animated piece’s five-second loop, Floyd’s face fractions itself into fractals, as pieces of himself break from the whole, spin around and whizz off-screen before exploding back in from the other side. By trying to examine Floyd’s specificities, we’re really pushing back against the force it’s trying to exert. Floyd wants to be unstable. It wants to keep us ungrounded, our wishes defied. There’s an endearing smugness in how Floyd disregards whether its audience has an easy time understanding it. To that end, try observing this piece at its lone moment of pause, when the loop restarts and Floyd’s blue face reemerges whole, staring straight at you. Like a too-smart student giving a too-snarky answer, he wears a mischievous half-smile, as if he knows we want to deconstruct him. As if he knows just how obfuscating he can be.

Floyd himself has two faces: one, set against a white background, is composed of highly-detailed, hand-drawn shades of Fabiello’s “beloved blue.” The other is a shadow aspect, an outline-only black-and-white rendering of Floyd’s face but one devoid of all detail; it seems like a camera-flash after-image, and it appears fully for only a brief moment. Popping with contrasting colors, this dark Floyd might be seen as the ur-individual, the stripped-back self which precedes connotation, thought, or morality, but which accompanies us always.

Artist Fabiello, otherwise known as Fabio Ivan Albizzi, confirms this duplicitous notion, saying “Floyd is many things. He is the artist; he’s me as I would like to be or as others see me, but Floyd is also a mirror [for] you too, and whoever stops to look at him. What I wanted to evoke is the sensation of the multiplicity of aspects of the personality, the wonder and the magic behind a look, a thought, an idea in the making.” There’s a Buddhist undertone to that sentiment, that the self is being recreated anew in every refreshed moment. In that philosophy, the self is an evergreen thing, bearing only passing resemblance to that which immediately precedes it. Similarly, it’s hard to see Floyd’s Facets in the same way twice. Each time the NFT loops and Floyd builds himself back to whole, he’s become a slightly different person, a slightly different piece, with slightly more revealed, noticed, or understood. He has been changed intrinsically.

As a self-portrait, Floyd demonstrates an artist’s impulse to order their form into something solid, capturable. Fabiello just can’t quite seem to, however, reaching an ultimately-futile point where things — seen too closely — become mutable, shifty, exaggerated as if in a fun-house mirror. Nothing is stagnant, not the piece nor its shapes, its edges, its meaning. Not even its viewer. Remember, as you observe the piece through repeated viewings, you change indelibly as well. Only if we bring our eyes close, like looking for blemishes in a hand-mirror, can we get a minute sense of this piece’s composition.

If you do hone in closely on Floyd’s physical construction, however, you’ll see countless arcane, almost runic markings which give his blue face texture. This hand-drawn, comic-styled detail — which is also visible in the finger-quivering lines which form Floyd’s faces — is one of Fabiello’s signatures.

In fact, much of Fabiello’s training is “linked to drawing and comics, to pencil, nib and brush strokes,” all techniques common in comic and pulp illustrations. It should come as no surprise then that chief among his influences is the great, and tragically late, Italian comic artist Andrea Pazienza, an enduringly influential figure in Italian art, comic art, and 20th Century pop-culture (plus a friend/influence to Keith Haring).

Fabiello discussed having admired Pazienza, “Since I was a boy,” noting that, “[Pazienza] had an incredible hand, a very beautiful stroke and an innate ability to capture the movement, rhythm and energy of the figures.” Pazienza was famed for his mastery over the full continuum of comic art, his use of color and texture and mood, and for his iconic characters: the hedonistic blonde playboy Zanardi, or the preeminently tragic Pompeo, both semi-autobiographical men with much of Pazienza in their habits, their worldviews, and, in Pompeo’s case, their untimely demises.

Those characters of Pazienza’s share with Floyd’s Facets an ability to capture multiple aspects of their artist’s personality in adjacent moments: the witty, well-loved and amiable Pazienza would often cede the next frame to a darker and gloomier version of the artist. While we can trace how Floyd might have evolved out from Pazienza’s influential lineage, Fabiello says, “I have not been inspired by others for this creation, and I am not good at inserting it in a particular artistic movement. I try to keep my expressiveness free from pre-established constraints.”

This sentiment is one popular in Crypto Art, a desire to create outside of preset constrictions of movement or form. “NFT art is the expression of a fast-moving world, that of cryptocurrencies and blockchains, something that is bringing innovation to society and the economy,” Fabiello said by way of explanation. “I like to talk about this world of blockchains in the works I do, and the contemporaneity [of it]…”

A powerful aspect of the burgeoning Crypto Art scene is how any piece designed for an online medium also explores these aforementioned issues, and they do so simply by existing in the way they do, uploaded on the platforms they are, viewed just as they must be.

Though there are some primitive VR galleries in which to observe Crypto Art, with many more in development (take Cryptovoxels, the rudimentary, albeit impressively functional, in-browser metaverse designed for artists to display their works), the vast majority of Crypto Art — NFTs of any kind, really — are observed either within an owner’s wallets or in settings which dominate the screens they’re on. Seeing an NFT in its natural online ecosystem and walking into a museum — a physical space dominated by sterile floors, high ceilings, guards in suits, and many, many, many pieces hung up on white walls — are fundamentally different experiences.

Here, online, there is no divide between a piece and its environment. Even a webpage like MOCA’s gallery cannot be extricated from the broader web environment in which it operates, the symphony of tabs and pages interlinked within the browser. We have only two options with which to observe a piece like Floyd’s Facets: viewing it “in-browser,” alongside all the other pieces generated on the same page, or in “full-screen,” where it fills its entire world, with edges that extend end-to-end, tip-to-tip.

Thus, there’s an inherent enormity to any piece seen this way, limited in scope only by the screen on which it is viewed. We can’t minimize the ability of a piece like Floyd’s Facets to dominate the environment it sits within. And for it to successfully express the big ideas behind it, Floyd must take full advantage of its existence in the NFT medium. It must remain out of the viewer’s control in order to be successful, i.e. you can only get so close to it while it automatically loops, thus safeguarding the nebulousness so central to its intention.

“Big Ideas” is perhaps an understatement. “This kaleidoscopic dance of correspondences,” Fabiello says of Floyd, “between light and dark, between truth and lie, between waking and sleep, between what is above and what is below, is basically life itself; this work can be read as a metaphor for the flow of existence.” The flow of existence is huge and sprawling and messy; so is Floyd. And as a piece attempting to express a number of fundamental dualities, Floyd presents multiple crucial interplays for examination: between observer and observed, between outward movement and inward change, between fragmentation and the multiperspectivism which affirms it. Floyd is a dance, a twirling waltz from extreme to extreme. It cleverly keeps from being any one thing at any one time. It has bits of many things in every pixel.

Elsewhere in his oeuvre, Fabiello isn’t as overwhelmingly ambitious. “In…subsequent works, I landed on the remake of great classics [in] the history of art, reinterpreting them with my style, and inserting them in a contemporary context, often with references to the crypto world.” Those pieces, all minted since Floyd was in April of 2020, also express an interplay, though one between classical values and the contemporary crypto ecosystem. For that reason, they’re somewhat easier to parse through, since they at least allow us a specific springboard with which to examine them (for example, one piece plays off the name and composition of George Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte). But Floyd’s Facets — which is itself the most complex and successful member of a larger series — manages to skim the enormity of abstract art without being exceedingly abstract in the first place.

In other words, Floyd is not readily cubist. Nor dadaist. And it isn’t minimalist either. It’s not meant to confuse or confound or misdirect. This piece, part of a larger communalistic trend in Crypto Art, is designed for connection and mutual experience. “I believe that the sphere of emotions is the realm of a work of art…Something should move…in the inner sphere of the beholder, [creating] a bridge through which colors, traits, shapes can flood the intimate space of the observer,”

In other words, Floyd is meant to be felt not befuddled over. Forgive me for befuddling anyways.

By Maxwell Cohen

Thoughts? Ideas? Find us here: https://forum.museumofcryptoart.com/