And his Generative Collection, Gazers, is an Unprecedented Exploration of Time, the One Thing that Binds Us

I: Two Converging Timelines, Leading to This

On a brisk, clear evening, two figures stand out on the lawn of a gently-lit house in suburban Chicago. It’s a boy with his father, their hands stuffed in their pockets, their necks craned towards the sky, both gazing up transfixed at the moon.

Decades later, Matt Kane tells me about the moments when he and his father would look up at the same sky, feeling the same wonder. “If I happened to go outside and look at the moon, it was one of the times my father would come out and look with me, and then tell me…how different the sky looked when he was a child…how you could see the Milky Way and so many more stars.”

Kane expressed little doubt that these quiet nights stargazing and reminiscing with his father, as well as frequent visits “to planetariums and science museums” ignited his lifelong fascination both with “the moon and stars,” and with more spiritual enigmas: “What came before me,” for example, “and the nothingness of black when you close your eyes.”

We’re here in my childhood bedroom. Winter, 2010. The clock reads 3:30am, but the boy — me — on the bed is nevertheless wide-awake, his eyes trained on the glow-in-the-dark galaxy attached to the ceiling. Within this mass of adhesive-backed decals (placed lovingly by his parents ten years prior) are stars arranged into constellations, comets with long tails and ringed Saturns of varying sizes, their cosmic majesty reduced to pieces of translucent plastic stuck to the dry-wall.

Like nearly every night in this torrid, months-long stretch of sleeplessness, the teenage Max Cohen lays in bed, lost amidst the false stars above him, letting galactic questions — Will the expanding universe continue expanding forever? How big can it get? What lies outside of its reaches? — transform into dwellings on death. How death is permanent. How that-which-lay-after-death is eternal. It wasn’t dying which my teenage self lost sleep fearing, but the infinite amount of time in which I would, in fact, be dead.

Through death, all humankind comes to confront infinity. Whether or not there is an afterlife whether or not we’ll sit at the foot of God’s throne, whether or not we’ll move onto consecutively higher planes of existence, our experience after death will stretch on into eternity. An eternity whose edges I could feel. An abyss that opened before and within me. The true terror of timelessness.

As sometimes happens in a given human’s history, certain leitmotifs continue to reappear until they become conspicuous. For Kane, that leitmotif is time, and, indeed, his life seems to be one of epochs.

The transitions between these epochs are not only sudden and unexpected, but dramatic. Afterwards, Kane seems to arrive in a fundamentally altered future as a fundamentally altered version of himself, which may be why he calls these moments “wormholes.” Like how at 22, Kane discovered the truth behind a lifelong lie relating to his health, leading him, quite understandably, to “become dissociated with my life at that point,” and into the wormhole he fell. “Within a month” of arriving on the other side, Kane “went to the best gallery [in Chicago], and I was actually accepted.” From the rubble of a crumbled life rose a new Matt Kane. The future from there took on a different hue.

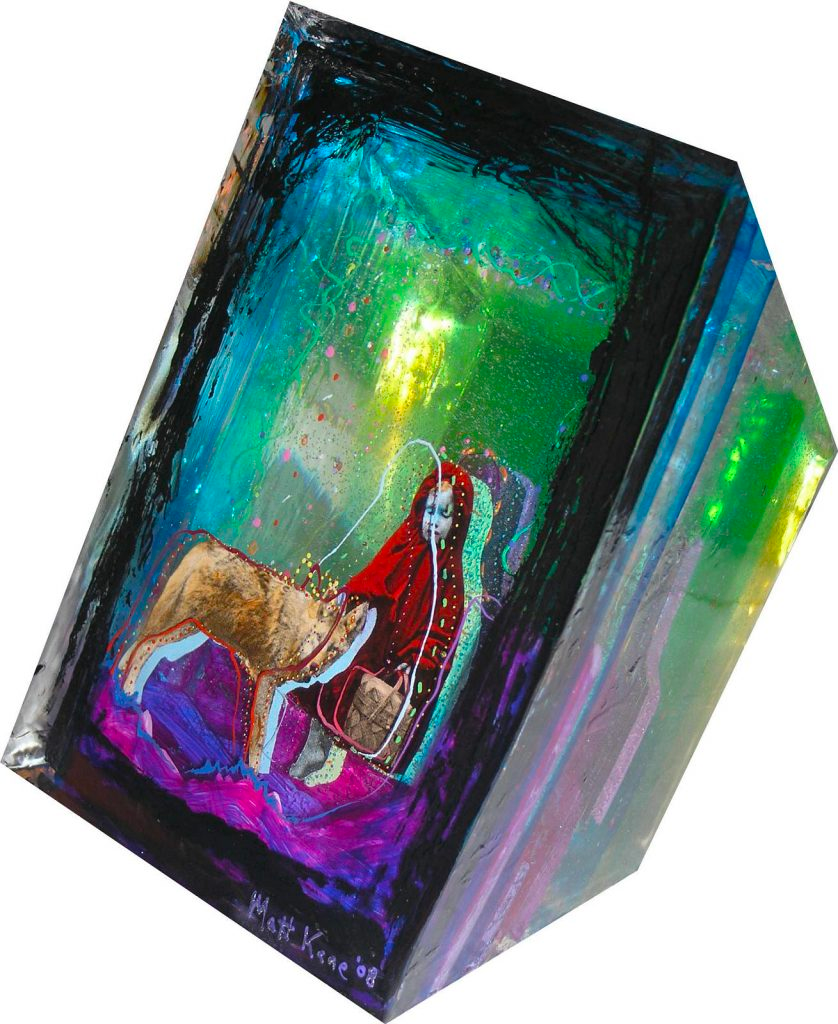

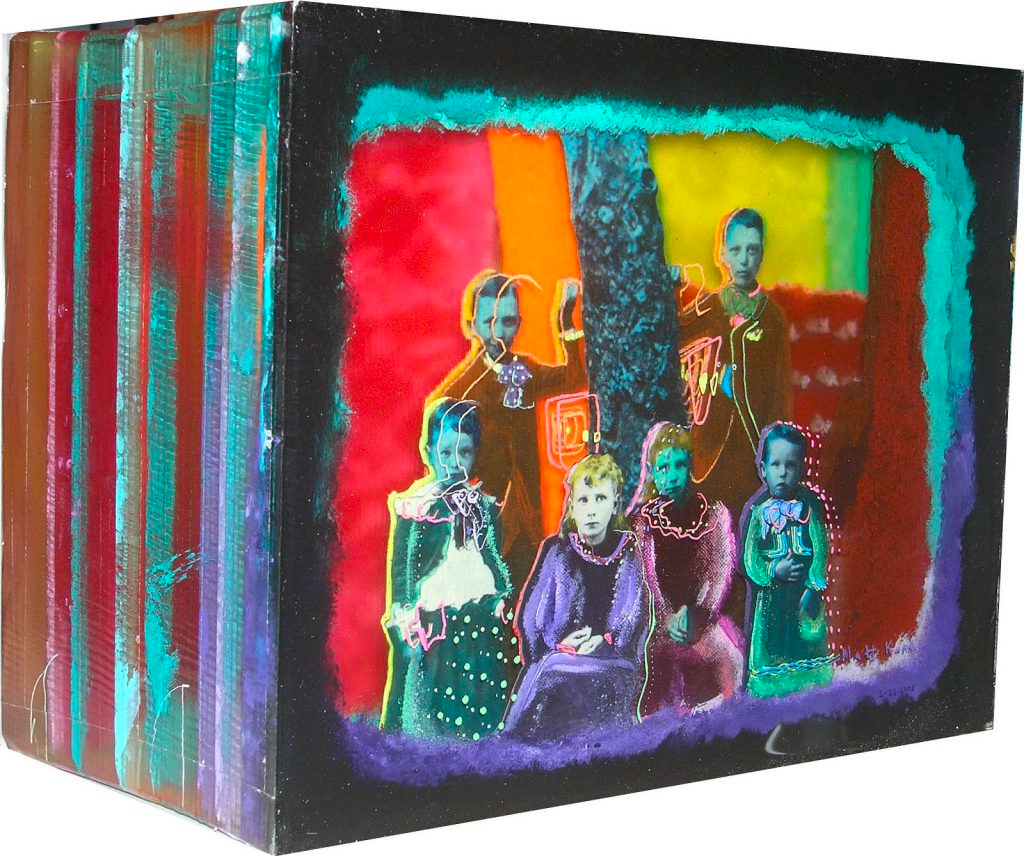

Another example: A few years later, Kane is “living in Seattle, in a design agency working my way up to become a web developer” so as to transition his artwork into a digital sphere. This was the culmination of a previous realization that “if I was to become a digital artist I had to build my own software.” Until then, he primarily built resin boxes, physical precursors to his digital art wherein Kane would press sheets of painted resin against each other to create layered 3D objects. But resin is a notoriously poisonous material, and so despite perfecting his process in 2007, he soon discontinued a physical practice altogether. His future digital work, however, would continue exploring both layering and color theory with newfound complexity.

In 2013, Kane left Seattle. “I had a friend who committed suicide…That’s when I began to create my own software and work on it everyday, to basically distract myself from grief…I don’t even start making art with it until 2017…and then I don’t come back out into the public with art until 2019.” Those first public art pieces, like the M87 Black Hole Deconstruction series from May of 2019, found Kane returning to the same concepts which had dominated his childhood: space and time.

Humans have no more connective single concept than time, I’d argue.

“No, no, it’s death!” someone cries from the mezzanine, “Death is what all living beings share!”

I respectfully disagree. Not in principle, but death is too abstract; few of us can bear to think about it directly, myself included. With time, however, we analogize death, can comprehend its scale, its infinity, its dread. “Time’s up,” says the Reaper. “You don’t have much time,” the doctor tells us. We don’t think about dying, we think about the short time we have left to live. We don’t fear our loved ones experiencing death, we fear the lifetime we’ll have to spend without them. Time is what binds us. We lust after it. It inspires our medical advances and our Faustian cautionary tales alike.

The issue with time, however, is that the two main mediums humans use to understand the universe — religion and art — do a crap job of conceptualizing it.

Some religions want nothing to do with time. Buddhism *very* basically says, “Don’t think about time, it’s not important! Exist exclusively in the present!” Most others, meanwhile, don’t actually deal with the reality of time, but things which supersede it — infinite Gods, eternal paradises — thereby situating their ideals outside of time altogether. Kabbalistic Judaism, for instance, asserts that only we mortals, who live in the lowest spiritual realm of Asiyah-Gashmi, actually experience time or space, tragically bound as we are to physical existence. So it seems religion can’t venture into time, it either lords above it or pushes it away. Which leaves us with art. But art, through no fault of its own, lets us down.

All art, after all, is finite. Songs end, books have a last page, films have run-times. Performances are ephemeral by nature. Artisanship fades: A beautiful chair decays, architectural marvels crumble, even the Colossus of Rhodes fell into the sea, eventually.

In the 1900’s, artists at least began experimenting with ways to approach time conceptually. In David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, a recurring motif of annular fusion (the nuclear process which powers stars) is emblemized in an ending which feeds right back into the book’s first line. A cute idea, but, come on, who’s reading that book more than once, anyways? Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 masterpiece, Rashomon, tells a single story from multiple perspectives, jumping backwards and forwards through time. Christopher Nolan’s 2000 film, Memento, unfolds entirely in reverse. Harlan Ellison’s 1967 short story, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” uses sci-fi narrative to explore the horrors of eternal life, but in this and other modern examples of immortality-cum-nihilism — be it Rick and Morty or Everything Everywhere All at Once — the power of the message is ultimately constricted by the medium.

Perhaps it is impossible to truly communicate the largesse of time through art. Perhaps some fundamental truths are simply too huge to confront anywhere outside the depths of our soul, and we spend our lives trying not to be consumed by them.

Kane’s initial artistic exploration of time was more a flirtation. Consider his emulations of Claude Monet. In Irises After Claude Monet, Stack of Wheat After Claude Monet, and Water Lilies After Claude Monet, among others, Kane emphasizes and embodies the central Impressionist ideal: to capture specific perspectives of the world in specific moments. Monet created some 30 paintings of haystacks, more than 30 of the Rouen Cathedral in Normandy, and countless of his estate at Giverny because he was obsessed with detailing how individual locations changed throughout different times of day and different times of the year. Kane modernized the sentiment while still working within it.

But he soon sought not just to study time, but to use it as an actual artistic tool, doing so in “…an artwork I created called Right Place & Right Time, which was 24 layers [of color], each of the 24 layers synchronized to the 24 hours of time in a day. Their location, their rotation and everything was synchronized to Bitcoin volatility for each hour.” The artwork still changes daily, with Kane aiming to eventually mint the 210 most historic days in Bitcoin’s history, reaching all the way back to September 2013, far before the artwork’s inception.

We mustn’t overlook that this piece’s many and momentary compositional shifts would all be impossible if not for Kane pioneering a digital style where individual layers could all move independently from one another. But they could, and so they can, allowing Kane to tackle extensive temporal concepts like Bitcoin volatility or “how a society values this new crypto economy” over time.

But even that buries the lede. Both Right Place & Right Time, and the gargantuan achievement which was to follow, were only possible because — as Kane told me with an air of finality — “Blockchain is timestamps, it’s timestamps and data. Some of the data is price, but most of the data is timestamps. And block time? It’s a clock, it’s a giant clock.”

II: Gazers

By December of 2021, I’d been investing in silly Solana PFP projects for about four months, so, yeah, I knew basically everything about NFTs. Like, for example, that the floor price always comes down after mint. So even though crypto art is abuzz discussing the latest Art Blocks project, a mesmerizing collection of 1000 pieces I’d been ogling all day, I decide to hold off on buying one. With ETH still above $4000, their .7 ETH floor price felt like quite an investment. Anyways, the price would come down. Price always come down.

I didn’t yet realize that Gazers, Matt Kane’s aforementioned project, was the gargantuan achievement I would soon understand it to be. And I didn’t realize it the next morning either, after finding the floor price had doubled. It wasn’t until many months later — with holders still posting their Gazers daily, with the collection maintaining a floor price of ~30 ETH, and with few pieces ever for sale (even today, in March 2023, only 40 of 1000 Gazers are listed on Opensea, only 10 of them priced within 50% of the floor) — that I realized something unique was afoot here.

Unique is an understatement. I now believe that Matt Kane has crafted not just a crypto art masterwork, but artwork deserving a pedestal in the hallowed halls of all art history. Because Gazers isn’t just drop-dead gorgeous, decadently thoughtful, or something which exposes the intricacy of its creation both on its face and in its gut. Gazers may be the first artwork to mimic the infinite expression of time itself. When the worms bore into us, when our cities fall, when humankind has proliferated throughout the galaxy, bred with Andromedan aliens and become unrecognizable, Gazers will remain, changed, always changing, just as meaningful to that unforeseeable, faraway generation as it is to ours today.

Kane smiled as he called Gazers “generationally-experienced work. This generation is meeting it this way, the next generation will meet it in a different way, and on and on because of what I’m doing with time.”

Time. When Matt Kane conceived of Gazers, it was under the impression that his own time was almost out. “A doctor told me some really poor news about my health,” he said, “and it made me believe I had a limited period of time to really create a masterpiece. If I’m going to create a masterpiece, I have to create it now.”

This happened a little over a year after the release of Right Place & Right Time. Having spent so much time enveloped within Bitcoin price volatility, moment after moment, day after day, instantaneous and extreme, Kane “felt my own relationship to time had become very chaotic.” So, he thought, “I’m going to create a project that is the complete polar opposite in terms of how it deals with time and change.”

Thus, he turned once more to the sky. “Since the dawn of humanity, the Moon’s phases have fascinated humans, influencing any number of activities on Earth including ocean tides, seasons, harvests, migrations, hunting, crime, sleeping, sex, and has inspired countless works of art…Our Moon has been imprinted across all our ancient and modern cultures,” Kane writes in his description for Gazers. “On the surface, Gazers functions as a lunar calendar, algorithmically synching closely with Moon phases in the sky, joining the blockchain with one of humanity’s longest running lineages in art.”

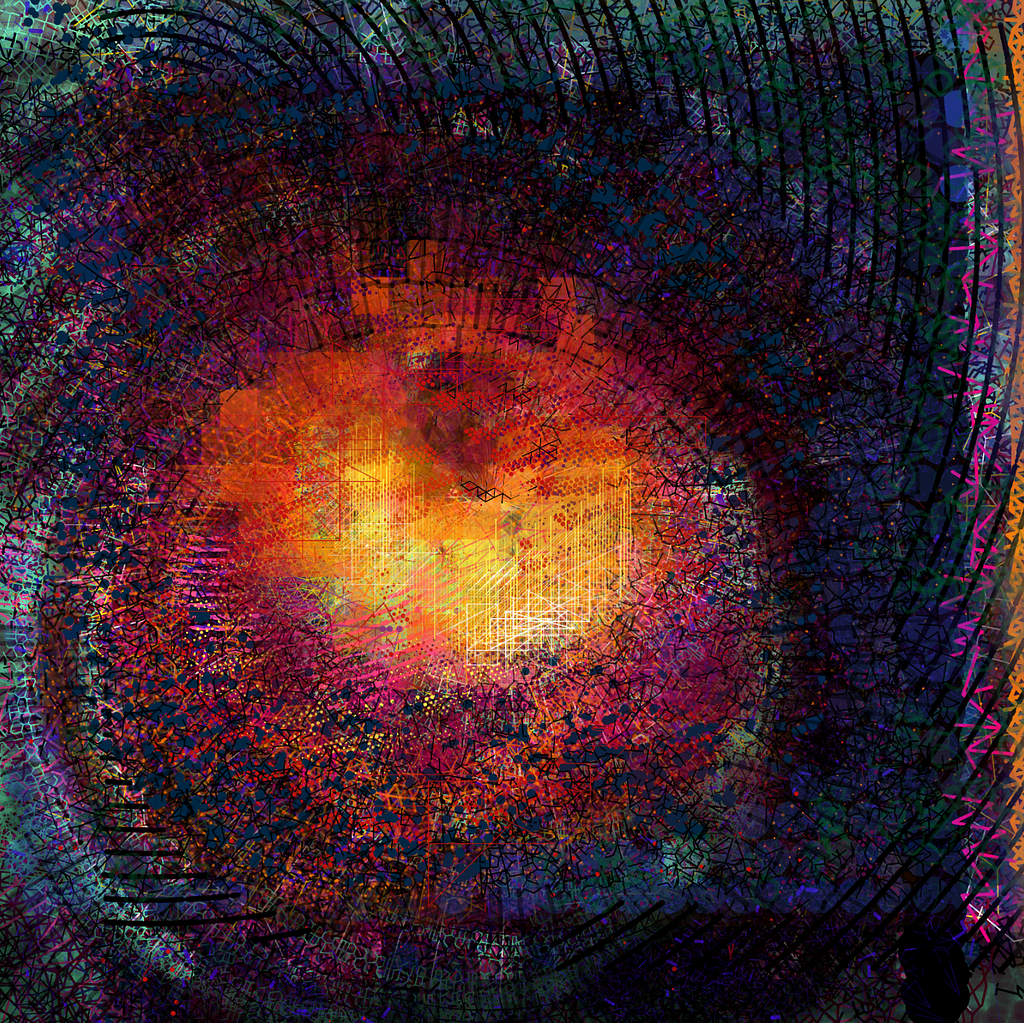

I’m tempted to try describing Gazers aesthetically, but just as when talking about time, language is too limited to capture its essence. I suggest you read the Gazers FAQ if you seek further context, but for our purposes, it’s better if I just show you:

Kane says he “created Gazers to be like a living artwork, to be lived with, and to not only have the artwork evolve over time, but also the appreciation and experience of viewers.” And Gazers are literally always evolving. In minute ways, Gazers change every single moment: You can see the slow, unceasing revolution of their lines in real time, for example (click on the link for any of the Gazers above). But also, “each day at midnight, [every Gazers] receives a new set of rules in terms of how to rise or shine over the next 24 hours, [resulting in] color that rises and sets, echoing the change of light in our sky,” Kane notes. Some days, that change is quite subtle. But on special occasions, this means stunning aesthetic shifts, like on New Year’s Eve, during an eclipse, or on Stephen Hawking’s birthday, where the fundamental design of each piece spends 24-hours in unrecognizable flux.

One need spend only a short time studying Gazers before it becomes evident that in the five-to-six months Kane spent creating and coding the collection, he included a level of complexity alien to most any other artwork. Gazers positively ooze secrecy, with hidden algorithmic triggers that take hold on unpredictable dates and cause unforeseeable changes, with the speed of each piece’s internal movement increasing bit-by-bit every day (according to a randomly-generated internal formula), and with encoded connections back to important dates in Kane’s life. These important dates are expressed as traits in each artwork: “Origin Moons,” Kane calls them, and they range from the date of his first ever art sale, to the infamous day in which a Sotheby’s buyer backed out of a sale for his piece, Meules after Claude Monet (below), an Origin Moon which Kane christened “No Sale.”

Virtau, collector and enthusiast, assembled a “Gazers 101” collector guide to catalogue all the collection’s known intricacies. Kane himself was motivated to create a dedicated Discord channel because his collectors were so rabid for a place to unravel and discuss the enigmatic artworks. “[The community] recently found that the M key unlocks the Claude Monet and Mary Cassat modes,” he told me, “which were only unlocked on each of their birthdays last year.”

Every bit of Gazers’ technical brilliance would be impossible if not for the blockchain’s time-keeping foundation, But with it, artists can code their artworks to change in perpetuity, some changes taking place once a day, others once an hour, once a decade, once a millenia. It’s possible that, 100 years from now, Gazers will still be in the process of unveiling themselves fully. We can’t know, and Kane surely won’t tell us. What he’ll say instead — cheekily, I might add — is, “All my work is really about transformation, as an artist it’s all about transformation, it’s all about change, it’s all about time.”

III: Eternity (as minted on the blockchain)

After writing the penultimate section of this article, I opened a random Gazers and watched it for a while. I soon realized that it was Gazers #0, the very first one minted, housed in Kane’s own collection. This one is a circular moon for now, but is coded to change its shape every month. Every month…until the end of time. Bathed in the Aurora Borealis’ glowing neon green, Gazers #0 reminds me of the ceiling in my childhood bedroom. It suggests the same questions. It contains the same sweeping sense of scale.

I got to thinking about who would inherit this piece after the artist’s death. Would it be passed down — through Kane’s line or another’s — from person to person, a family heirloom to be displayed in houses and apartments and underground doomsday bunkers for centuries, on spaceships, on different planets? I looked at Gazers #0 and felt my stomach twitch, burble, and open. From within it came a feeling I know well, the same one I spent teenage nights consumed by. Here it was again, though not the bogeyman it once was, but an old friend of sorts, one I don’t get to see very often.

And Gazers brought him around again, let me get up real close and see his liver spots, his beauty marks, his clogged pores.

I called this article Matt Kane is Eternal because I think within Gazers is the prospect of true immortality for their creator. Maybe not Kane’s name, but the sheer amount of him which is contained within the work itself. Programmed into Gazers are the artist’s interests, the days of his own finite life which were most meaningful, an “understanding of color and relationship to color [bolstered] over the last 20 years of making color decisions” which are intrinsically his. To witness Gazers is to peek inside Matt Kane himself. “Of course Gazers is a conceptual self portrait,” he said. For proof, he pointed to his “ approach to [software] bugs as an artist: Bugs are the evidence of the human, it’s the paint drips…and when I discovered these bugs [in Gazers], I literally said ‘This has more meaning if I leave them in.’” And so he did. Meaning many of Matt Kane’s missteps are in there somewhere as well.

This is not the first time, however, that an artist has leveraged the blockchain’s ability to capture and communicate time. Many works minted on Async.art, like A Day of Soft Construction by Manards or Sundial by Vans Design, change based on the time of day, with various aesthetic states encoded into their very smart contracts. And 720 Minutes, Mactuitui’s Art Blocks collection, pioneered the idea of affixing an actual working clock to the blockchain, each artwork a kind of pulsating beat that dissolves and reforms every second.

Gazers are both an evolution and a culmination. “How will the future appreciate our ambitions and perseverance?” Kane asks in his description for Gazers. Who knows? Because our methods of admiring Gazers will naturally advance. Screens larger and of higher resolution will proliferate through the market. Say we enter the Metaverse. Say we wear AR contact lenses that project the internet out onto our waking world. It’s not that Gazers will always be there which is so exciting, but that these future Gazers will change with the times, will continue changing for all the times thereafter, forever in flux, facsimiles for eternity itself. Times after times, they will be there to accompany us humans as we embark upon the same spiritual sagas, pondering our same mortality, falling into the same wormholes again and again.

When we meet a handsome stranger on the train, thereby changing the trajectory of our lives, Gazers will be changing too. When we hear our newborn child cry for the first time, the universe may fundamentally recolor itself; Gazers will be fundamentally recolored as well. When we wake to yet another day of devastatingly blasé minutiae, time seeming to calcify even though our hair somehow gets longer, our teeth yellower, our fingers more calloused, Gazers will be changing just as slowly and inconspicuously as we are.

For within Gazers are all the possible expressions of life which eternity contains. Encoded into the fabric of our own existence is every possible move we can make, thought we can think, word we can say. Which begs the question: Do we have free will, or am I just jumping from one preconfigured state of Max-ness to the next? Does Gazers not ask the same question anew each day? In these artworks — hidden, perhaps, but nonetheless present — are all our fates, free wills, deaths, and immortalities. Or allusions to them. Things we know, things we don’t, and things we don’t have words for quite yet. All there, recorded forevermore by Mr. Matt Kane on the trusty, ever-tick–tick–ticking blockchain.

Learn more about Gazers at Matt Kane’s dedicated Gazers website, or peruse them yourself on the collection’s Opensea page.