It’s Up to Us to Make Sure it isn’t a Nightmare

1. A Brief History of How Things Are

By the time you read this, everything will have changed. From yesterday, from last week, certainly from the month before. It’s often said that “each day is a year in crypto,” but lately, things seem to be reincarnating anew every few hours or so.

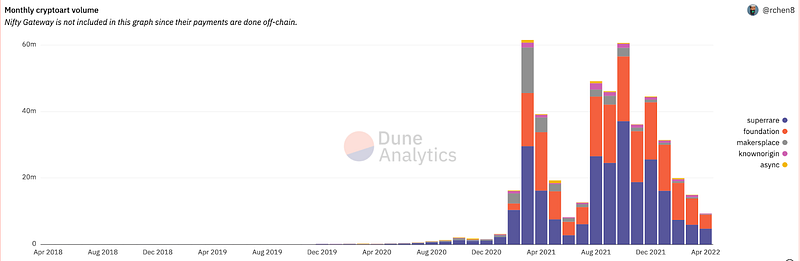

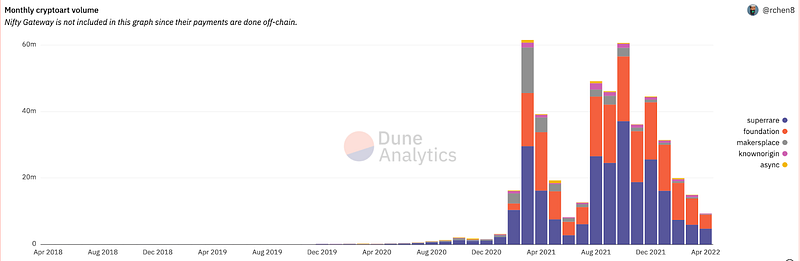

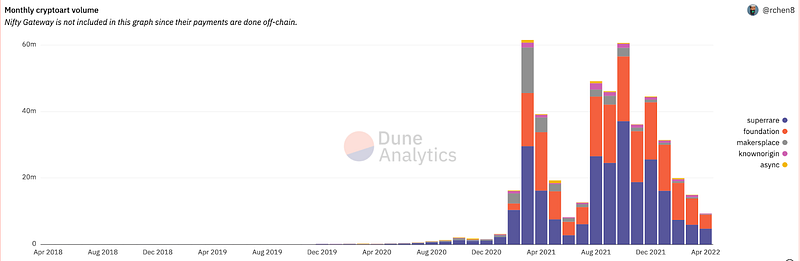

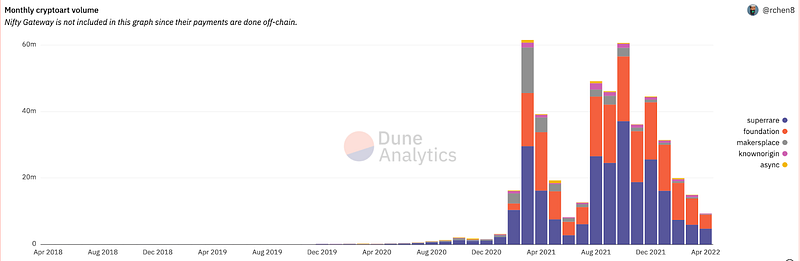

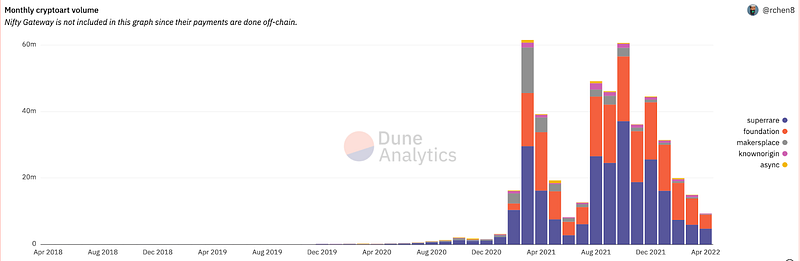

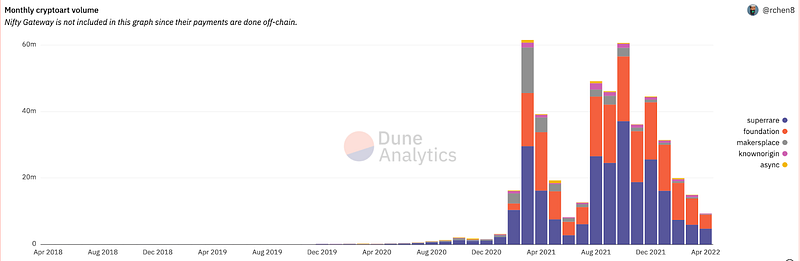

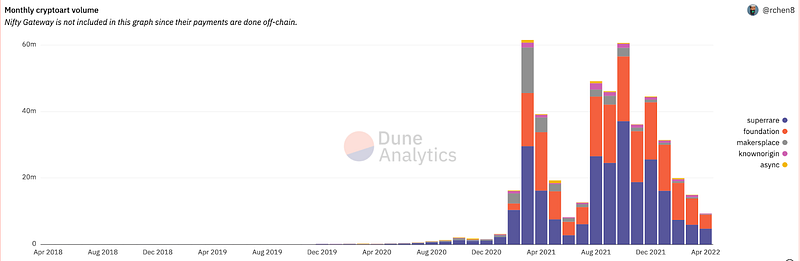

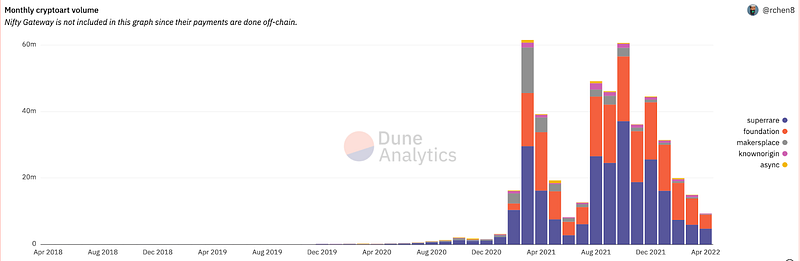

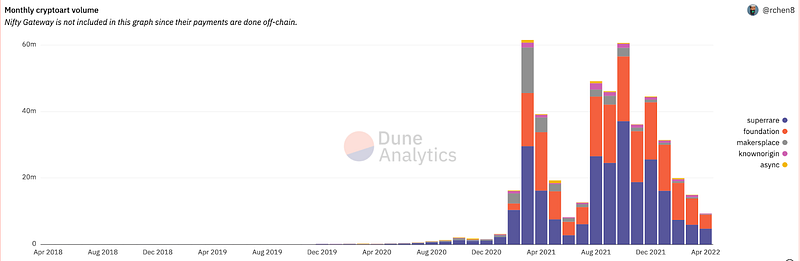

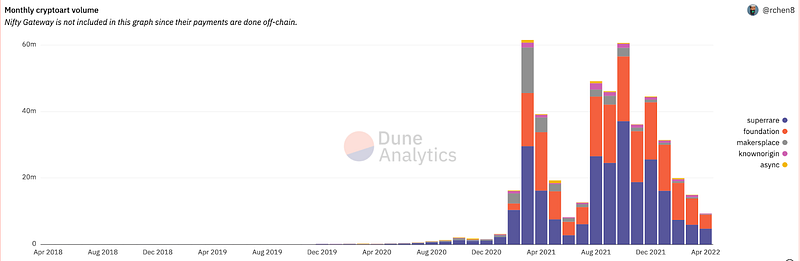

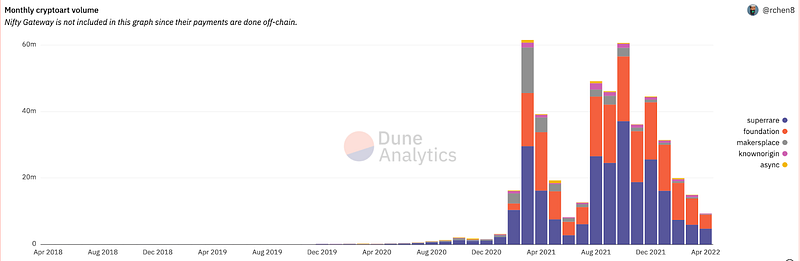

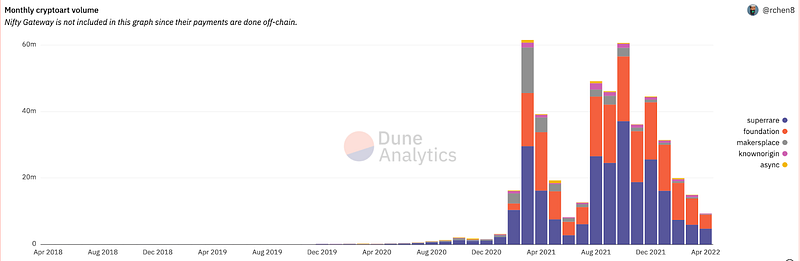

When writing this piece’s first draft, the whole NFT market was on a precipitous downswing. Now it’s back up. Last month, March 2022, 1/1 art was being bought at its lowest level since June/July of 2021, or at least that’s what Dune.XYZ’s data on Superrare said. But by the time you read this, eyes and wallets may well have drifted back to 1/1 artworks, everyone wanting to flex their new grails. Maybe the market is pumping as it never has before. I could have no way of knowing.

Because even though we understand how the crypto art space moves (liquidity enters into NFTs through the public-friendly portal of PFP projects, makes certain players quite wealthy, those players use their still-wet wealth to increase their social capital by purchasing crypto art, the price of editions and 1/1’s pumps, overall prices become too high for most collectors, and without a ready infusion of new liquidity, crypto art acquisition stagnates until fresh finances interfere) we have little grasp on when any given shift will happen. As it pertains to prophesying cycles of the market, we might as well be doing rain dances. We might as well be sacrificing goats. Perhaps because web3 is so international, or perhaps because the NFT market is so heavily segmented, predicting the market’s timing is almost impossible.

And if we can’t predict the machinations of a crypto art world we’re currently living in, then attempting to anticipate the progressions and pitfalls of future Metaverse adoption is like trying to shoot an arrow into a grape from 40 yards away in the dark.

Right now, Metaverse development seems to contain that same pervasive spirit of experimentation, community, and building which, I’m told, characterized crypto art in its infancy. But just as summer 2021 brought a sudden deluge of internet into crypto art and NFTs, when the rest of the world eventually takes note of the Metaverse, it will notice very quickly and all at once.

Thank God for DADA, and Matt Kane and Sparrow Reed and Alotta Money and every artist who signed the “Minimum 10% NFT Royalties — Letter to Platforms,” because were it not for their insistence that 10% artist royalties be standard on all NFT art sales, we might be without one of crypto art’s most important characteristics. In the fervor of mass adoption, such important considerations might have been ignored, delayed, or eschewed altogether.

Such characteristics are the product of anticipation and execution. But alas, we can only anticipate so much. And it’s terribly difficult to change norms once they’re entrenched.

In some ways, crypto art is perennially cursed to struggle against whichever forces it lacked the foresight to forestall. Like how, in Museum of Crypto Art director Shivani Mitra’s words, “There’s more VCs than users in web3 at this point,” or how crypto art lacks “marketplaces that curate for unique art, not crappy algorithms that pump certain artists and creators.”

With the Metaverse, we can do even better. We’re older, wiser, more experienced. We can take what we’ve learned from crypto art and apply it forward to this next great advancement in art. Nay, we must! Because egalitarian ideals must be put firmly in place before this thing really takes off, before impersonal actors enter in, before power is indelibly assigned. It’s too important for us to muck up.

The Metaverse could potentially change the shape and scope of artistry itself. It could fundamentally change how artists manage their careers, how art is seen and displayed, offer previously impossible experiences and connections, and radically redirect the entire artistic continuum, perhaps permanently.

But it could also conceivably evolve into an elitist hellhole of corporate stakeholders, psychological manipulations, and unchecked capitalism. It happened to social media, it’s happening to web3, and it’ll happen to anything that isn’t insulated against it.

Already, Meta (ugh) has announced plans to charge content creators 47.5% of all sales for the mere privilege of using their farkakte marketplace. See? It’s already happening. Before the thing is even here, they’re trying to take it from us.

Any day now, the Metaverse will properly blow-up. It’s vital that we think critically, communally, and immediately about what the Metaverse can be, what we want it to do, and how we can get it there. We’re still early. Let’s be early. We, those of us in the know, who are here now, can shape the mold the Metaverse will one day fill. We have choices to make about what this thing will become.

I’m here to help you start making educated decisions.

2. Unwritten Rules of the Game

Almost nobody can do what Refik Anadol does.

Anadol is a quintessential digital artist, someone whose work asks questions — about visual interaction, about perception, about data — only digital art could answer, which could only be explored in digital settings.

Anadol refers to himself as a Data Painter, reflecting how his art is created in lockstep with sophisticated AI models he and his team build. Anadol told me, “I couldn’t stop thinking about the machine as a collaborator, the machine as a friend, as a team member.” Naturally, this engendered questions about what exactly could that collaboration create, and how it could express itself. “Over the years, this idea became more and more profound. Can data become a pigment? Can data become a window, wall, a feeling, emotion, memories?”

But it’s what he said next which seems to be the coda to his work and his popularity.

“Eventually,” he said, “this idea didn’t fit into classical ways of exhibiting.”

It’s not that Anadol disrespects museum or gallery environments, he just doesn’t see them as having adapted well to the digital art revolution. “The classical role of exhibitions, galleries and museums may not immediately need innovation. They are not urgently needing to change the experience, create impact, generate new ways of seeing,” and because of that, they may seem superfluous to so much of the art being created today.

Walking through the halls of your average mid-century art museum, it’s hard to argue. We live in an eccentric artistic age, with our most notable works often being those which swing between zaniness and outright existential terror, something which reflects, in Argentinian artist Julian Brangold’s words, our “conceptual turmoil.” Do white walls and suited security guards and solemn spaces really reflect our modern artistic sensibilities? Not in my opinion. Traditional art museums are tombs. And crypto art swings from chandeliers, drunken, half-mad, naked except for a single sock (In some way, crypto art’s adoption of Twitter as its de facto home feels unavoidable: It’s the perfect place for a movement characterized by mania).

But Anadol’s work demanded a certain kind of grandiose and shapeshifting setting, and unable to find it via traditional exhibition models, he invented his own, presenting his art through what he calls “Immersive Rooms.”

These Immersive Rooms are immense spaces — cavernous and accompanied by booming, soul-throbbing sound systems — outfitted with cutting-edge projectors where Anadol’s hyper-colorful, dynamically-textured data paintings are blasted, dancing, onto every available surface. Erected in cities the world over, Anadol’s Immersive Rooms typically attract mass attention, like recently in Berlin, where, according to Artnet, “the line snaked down the block…to Galerie König on Tuesday night to see Refik Anadol’s new show…which is causing a small sensation among a cross-section of the public that does not normally show up at art exhibitions.”

Unsurprisingly, display is ever-prescient in Anadol’s mind. “How to display your experience?” he asked. “How to display your idea? How to execute an installation that has a meaningful, purposeful connection with your ideas? It’s always a challenge.”

The question of display is one that’s dogged digital artists since digital art’s inception. Though some digital works, like Lean Harmon and Ken Knowlton’s historical Computer Nude (Studies in Perception I) (1967), can be sensibly displayed upon aflat surface, the masterfully-detailed 3D sculptures of artists like Klara Vollstaedt, for instance, feel trapped behind flat surfaces, or at best diminished by them. Whether upon walls or screens, much digital art is imprisoned behind flatness, and that limits their ability to really immerse audiences as the artists intended. Almost like watching Mad Max: Fury Road on an airplane seat-back.

Anadol’s triumphant display mechanisms are the result of much trial, error, and experimentation. The result of the artist’s brilliance, absolutely, but also the institutional, economic, and technological investments which have been made in his success (a former artist-in-residence at Google, Anadol mentioned that Bill Gates is one of his collectors). One can argue that Anadol is among the world’s most-famous digital artists, or even just artists, period. He’s unironically been called “The Leonardo da Vinci of the 21st Century.” Many would argue that he’s earned a position in the digital art Pantheon.

Few artists can afford anything akin to Anadol’s experimental, cutting-edge setups. Few artists have access to assistants, studios, and institutional backing of any sort. Few artists can ask the questions Anadol asks, in the ways Anadol can, with the success that Anadol’s had.

Thus, few artists can conceivably connect to audiences as Anadol does.

Though Anadol is doubtless an artist of inimitable style and awesome skill, the truth is thaat there are countless artists of inimitable style and awesome skill in every generation. Their collective output, however, generally coalesces into the fortune of a few figures (Surrealism, Dali; Cubism, Picasso; Pop Art, Warhol and Haring; Contemporary Art, Koons and Jasper Johns). Those figures, of which Anadol is certainly one, receive the lion’s share of acclaim, attention, and most importantly, funding.

I said it before: Almost nobody can do what Anadol does.

And that’s an enormous problem.

Few artists can afford anything akin to Anadol’s experimental, cutting-edge setups. Few artists have access to assistants, studios, and institutional backing of any sort. Few artists can ask the questions Anadol asks, in the ways Anadol can, with the success that Anadol’s had.

Thus, few artists can conceivably connect to audiences as Anadol does.

While crypto art addresses and democratizes art’s visibility, authentication, storage, and acquisition, it fails to address this so-called Anadol Issue. Because most every artist lusts for unique and revolutionary ways to connect with audiences; that connection is how they make their bread, their name, their art come to life! Most every artist would benefit from access to the same technological suite Anadol has, tools with which they can use to tease out their fullest abilities. And it’s not just the art-making tools. It’s the kind of validation, both internal and institutional, which comes from seeing one’s art hung-up huge and high, which comes from audiences being awestruck by one’s work, which comes from having work contextualized in an auction house like Sotheby’s or Christie’s.

In other words, which comes from their art being experienced as opposed to just being seen.

During a conversation I had with the vaunted Italian crypto artist, portraitist, and Metaverse enthusiast Skygolpe, he spoke about the experience of purchasing art, of being in a gallery or an auction house with an artist, hearing them speak about their pieces and provide context about process or inspiration firsthand. “Everyone,” he said, “will want to acquire through an experience rather than being behind a screen.”

I think that’s been borne out. Sotheby’s recent “Modern and Contemporary Day” auction featured 12 NFT lots, bringing institutional legitimacy to a host of crypto artists, providing them a high platform from which to tell the stories of their art. One of those artists was urban climber DrifterShoots (Isaac Wright), whose physically freed and daring photography is impressive, but contains a far greater emotional heft when we learn about the past pain of a prolonged prison sentence. It’s no wonder his auctioned piece, Whatever It Takes (Where My Vans Go #119), sold for nearly 20-times what it was estimated to.

Also represented was CathSimard, the brilliant landscape photographer, who was recently dragged into a ridiculous controversy when Twitter user @CryptoPunk4052 tweeted, “The NFT market does not mirror the art market. There’s a speculative bubble that propelled amateur art to unreasonable prices, for instance the late Ren Hang’s non-NFT photos can be purchased for $10–20k, whereas an amateur photographer such as @cathsimard_ with an NFT will too.” Naturally, this tweet drew a lot of ire. Because by clinging to traditional tactics of institutional legitimacy (i.e. this artist matters because these people said so, and this artist doesn’t because of some ingrained sociocultural bias), the tweeter totally minimizes and disregards Simard’s stunning work, technique, and style.

But I would argue that merely appearing at Sotheby’s has, in a roundabout way, the same effect.

Yes, in a vacuum, the Sotheby’s auction was wonderful for those artists, just as it was wonderful for crypto art in general, exposing artists like Claire Silver and LIŔONA and Defaced to a different class of collector. But only 12 artists were lucky enough to have their art displayed in such a setting. And when artistic talent is validated not inherently by their aesthetics but via the influential opinion of exclusive institutions, that’s bad for art. Whenever outside forces act as automatic legitimizers, the less artists, even the great ones mentioned above, are judged for their content and more on the basis of where their work has been, who owns it, and who has deemed it worthy.

All of which sequesters success away for the few and keeps it from the rest.

True democratization of art requires true democratization of all its various extremities, too. But right now, institutions exclude the majority of artists. Monetary considerations exclude them too. As do all the limitations of scale, scope, presentation, material, context, and attention which only a few artists every generation are able to transcend.

But only 12 artists were lucky enough to have their art displayed in such a setting. And when artistic talent is validated not inherently by their aesthetics but via the influential opinion of exclusive institutions, that’s bad for art.

What the Metaverse theoretically offers is an antidote to all of these things. It’s a panacea. It’s a final destination for digital art. In hindsight, crypto art itself might be seen merely as a waypoint.

3. How to Play

Understand this: The Metaverse is not a single place. Not really. Not more than “the internet” is. And it doesn’t necessarily necessitate a VR headset (although visiting the Metaverse on a browser is like searching the web on a Nintendo Wii). In actuality, the Metaverse is a comprehensive collection of worlds, experiential environments, and interactive planes, or, as per a tweet by the legendary Belgian 3D artist Natural Warp, “Metaverse is a term for ALL ‘places’ in the digital world,” with each place akin to a webpage, each useful for different things, each appealing to different people.

As it would happen, I’d sought out Natural Warp’s expertise for this piece just weeks prior.

Warp found his specific brand of “360 art” almost accidentally, having seen 360-degree photos proliferating through Facebook in the mid 2010’s and wanting to explore the form. He, a digital art journeyman, used 360 art as a way to capture the “feverish dreams [I had] as a little boy in kindergarten.” Fully three-dimensional, Warp’s kaleidoscopic works are interactive, too: You can walk completely around them, and often step inside.

For years, Warp was relegated to seeing his creations only on a 2D surface. VR technology changed that. After acquiring an early HTC Vive headset, Warp was able, for the first time, to experience his works as if they were real objects: huge and imposing and there, right in front of him.

“I can say without shame, I just started crying… I mean if you’re already doing 20 years of digital art on your screen, and you never step inside it, then you cannot imagine what it does to your body…You literally shut down the world around you because you’re placing the VR headset on your head…It’s visually and auditively a complete new world, and you know you just created it out of nothing.”

I’ve been to see Warp’s works in Somnium Space, and the effect is stunning. It’s hard to communicate the gravitas his pieces carry — which so many pieces might perhaps carry — when you’re seeing them surged to the size of a house instead of shrunken to fit a screen.

And that’s the point.

Natural Warp has been able to find financial success and social significance largely because he used novel Metaverse technology to showcase his art in its purest, most accurate, most immersive form. He builds in VR, displays in the Metaverse, and has made his name doing it.

“I can say without shame, I just started crying… I mean if you’re already doing 20 years of digital art on your screen, and you never step inside it, then you cannot imagine what it does to your body…You literally shut down the world around you because you’re placing the VR headset on your head…It’s visually and auditively a complete new world, and you know you just created it out of nothing.”

As did Metageist, another progenitor of the form and an early adopter of both VR and the Metaverse. Like Natural Warp, Metageist was a long-time digital artist. He worked in graphic design for nearly 20 years before stumbling upon VR technology.

He’s been touting the Metaverse’s incredible capabilities since at least 2019, when he gave a TedTalk on the subject which featured him creating art in real-time using Tiltbrush on his HTC Vive. He’s seen it played out first-hand, how astounding and significant one’s work can appear when just shifted into a Metaverse environment.

“Even just seeing artwork up on the walls of a pretend gallery on a flat screen elevates it more than it just being in a website or just being on a smartphone screen,” Metageist told me before relaying a story about how he did “…a workshop with a bunch of pensioners, like 70 and 80-year-old men and women…retirees from a care home who were doing watercolors, and I made a mobile [VR] arts gallery for them and it completely blew their minds, and it was the most exciting thing they’d ever seen. Because their little watercolors were now 30-foot prints on the walls of a giant gallery space.”

In the Metaverse environments that Metageist and Natural Warp work in, artists can theoretically create and present their work with the same astounding scope that Mr. Anadol does, but without the prohibitive cost. A $300 headset (and the price will come down in time), plus the cost of a sufficiently-powerful computer is an astronomically different proposition than the six/seven-figure AV rigs one would otherwise need to achieve the same end.

And in certain circumstances, with the right clientele, it provides the kind of powerfully-connective experience that digital artists can otherwise only dream about. Skygolpe told me about his first Metaverse exhibition, held in Somnium Space in collaboration with a fledgling M○C△, where “We broadcast on Twitter the live tour, where I was there, my avatar was there, the curator was there, the host was there, [Colborn Bell] was there, and we were all in different places of the world, but somehow, because we were all using headset, it was really like feeling this experience of being there.”

Yet we’re still talking about what are, in my opinion, the Metaverse’s very entry-level effects on art.

Natural Warp pontificated not just on what levels of immersion VR and the Metaverse currently allow, but what will become possible in the future should the tech become widely adopted and developed. “We’re not going to be only visual artists and auditive artists, but we’re going to create emotions or recreate combinations of emotions by using this tech…The experience that you have, the emotions you feel when experiencing [art]…those are only [from] two things, visual and auditive. If you can add to that, for example, tension or warmth or cold or even breeze of air, or smell or other electric impulses…if you have a tool set that can bring you as a creator beyond that, it’s going to be, like I said, indescribable.”

He wasn’t the only artist I spoke to who became giddy at the idea of the Metaverse’s long-term implications. Skygolpe used the phrase “life designers” to describe how, in a Metaverse environment, “You will basically create virtual spaces and virtual experiences which in my opinion will be one of the most intense forms of art. Because it’s not only about watching a piece of art but about living a piece of art.”

We see examples of this already. Like Monaverse, where interactive digital environments can not only be built visually, spatially, and auditively, but then tokenized and sold. Metageist recently sold his first Monaverse space, The Spinnerette, an incredible snowglobe array of starry skies and neon platforms which contains “6 interchangeable sculptures, 7 NFT canvases, 2 portals you can edit to point to any space in the @monaverse, and bespoke ambient score by @SigilAudio.” This “artwork,” purchased by collector Protocollabs_1, is an entire internal ecosystem, something beyond what even the most advanced physical installations can do, and somewhere theoretically accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world.

“Things like that, there’s no restrictions in terms of scale,” Metageist said “And that sort of stuff, the creative freedom you get once you understand the tools for creation is just, like you say, unprecedented.”

When we affix artists with the ability for unprecedented expression, how can there be any other outcome but a boom in creativity? And when we experience a boom in creativity, how can there be any other outcome but an influx of interest, attention, and connection?

Crypto art itself is a prime example. Just look at the massive mountains of creative output we’re privy to seeing every single day, from artists all over the world, responding to subtle social shifts in real time, and all because tokenization gained prominence and acceptance. And with this output, an exponential increase in how many people care about art and want to support the artists which create it.

When you’re only exposed to art through sporadic museum visits, jaunts by a gallery window, or the odd news article discussing an 8-figure sale, it’s hard to feel visual art’s tidal pull too powerfully. And even so, we usually experience such works with the hair-trigger attention of a passerby, without feeling any sense of connection with the artist.

Crypto art somewhat addresses that problem, but it’s still difficult to forge any kind of genuine connection with artists through sporadic Twitter interaction. And for the layperson? Highly unlikely.

Metaverse environments, meanwhile, allow for what feels like face-to-face interaction, and between parties unperturbed by physical location. Skygolpe said “When you’re in the metaverse, you really have the feeling that you’re there, and somehow your mind tricks you and it’s almost as if you are outside in the street, so your psychology works on a more interactional level.”

Interaction is, in my opinion, the skeleton key that reveals the Metaverse’s potential. An accessible, user-friendly Metaverse changes the way every aspect and actor in the artistic process interacts. Artist with art. Art with environment. Art with audience. Artist with audience. Environment with audience. Art with art history, even! Any constraints upon where art can be seen, how it can be presented, and how we connect to it are all made moot.

And we can’t begin to predict the ripple effects this will have. An explosion in art collection? A newfound economic windfall for experiential art? A complete reimagining of how art is curated, coalesced, and exhibited? Schoolchildren no longer interested in being Youtubers when they grow up but art collectors, art curators, artists themselves?

It almost seems too good to be true, doesn’t it?

Potential is always too good to be true. David Foster Wallace once wrote “Talent is sort of a dark gift…talent is its own expectation: it is there from the start and either lived up to or lost.” Potential is exactly the same.

In the case of the Metaverse, however, wasted potential might mean much more than just a loss.

It might mean the undoing of everything crypto art has fought for.

It might mean the death, in no uncertain terms, of everything we hold dear.

4. Simply Walking Into Mordor, and How Not to

Potential has fangs; what happens if it bites back? A new arena for art, meant to usher in a new age of creativity, what happens when it becomes corrupted, tainted, exploitative? All things cast shadows, and the Metaverse is no different.

I know that sounds fatalist, but anytime technology is adopted without sufficient safeguards, there will almost certainly be unforeseen and potentially cataclysmic consequences.

Think early social network era, and the eventual rise of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram. Nobody at the beginning seemed to put much thought into data privacy (or perhaps they simply didn’t care), or about free speech and how questions of it could be politicized, or how social media’s targeting of teenagers might correlate with an eruption in teenage suicide, now the second-leading cause of teenage death and a number which has been rising steadily each year since social media’s mass adoption 2007.

To change social media now would require Herculean effort, which neither CEOs nor Boards of Directors nor the Federal Government itself seem especially interested in exerting. The time to “fix” social media’s ills would have been when it was still small and malleable, before social media companies were multi-billion dollar bureaucracies with multinational tendrils.

It is our responsibility as Web3 pioneers to delve into the Metaverse as much as we possibly can, as soon as possible, as often as is realistic, because we are still early enough in the Metaverse’s development that it can be reshaped and reoriented with relative ease. Early enough to redirect rudders and trim the jibs, so to speak. We must take responsibility in guiding the ship to safe harbor.

Ours is a still-fetal Metaverse, just beginning to develop fingernails, still a ways from public adoption. Why? Because it’s clunky. In Metageist’s words, “It takes 20 minutes to update every time, and you generally need a good PC. You need a cable. You need a big headset.” And it’s cost-prohibitive. And the UI is quite far away from anything the layperson could intuitively navigate.

It’s like Facebook before there was a like button. It’s Twitter pre-retweet. It’s Iphone without an app store. Social technologies all, but devoid of their most defining features, and thus still in the domain of the experimentalists and the builders.

Of the artists I spoke to, Anadol was the most outright dismissive of current Metaverse technology. Although he admitted that he loves the Metaverse in theory (and he’s even developing an artistic ecosystem there, DATALAND), he said “I do not believe the current technology is creating any level of engagement. Truly. Not gimmicky…I’m not against the Metaverse. But I cannot fool myself to say that the VR devices we have, or virtual experiences are really the ultimate experience. I do not believe that. We are just using our capacity of technology to justify an experience.”

At some point, however, that will cease to be the case. Apple or Google or another tech giant will storm the market with their VR-headset-of-the-future, and it will be light and easy-to-use, integrated with all your favorite apps, and freakin’ awesome all-around. The cost will be stomachable. The worlds will be rendered beautifully. Multifarious experiences will draw the masses into the Metaverse’s many worlds.

And by then it will be too late.

So before that happens, we need to be saddling ourselves with Metaverse technology: buying headsets, downloading apps, going to Somnium Space dance parties, visiting CryptoVoxels plots, experiencing Monaverse worlds. We should be seeking out and supporting Metaverse art, initiating Metaverse experiences, and learning about the tech.We need to see what happens when the Metaverse enters into a culture and dissolves into its bloodstream. Before established players are too big to fail. Before there’s enough money coming in from elsewhere that the core enthusiasts and original adopters can be ignored.

So before that happens, we need to be saddling ourselves with Metaverse technology: buying headsets, downloading apps, going to Somnium Space dance parties, visiting CryptoVoxels plots, experiencing Monaverse worlds. We should be seeking out and supporting Metaverse art, initiating Metaverse experiences, and learning about the tech.

We need to get users accustomed right away to the non-negotiable features we hold dear: quality of experience, affordable land ownership, profit-sharing, data privacy, architect royalties, etc.

M○C△ founder Colborn Bell mentioned recently in an interview with Fortune how he believed that, “Digital land is a non-scarce and non-valuable asset in the Metaverse. And…I do not think that it is necessary or a prerequisite to be involved in these worlds in any way, shape, or form…Leaders of the future will be those that provide that space for people to express themselves in this…spatial web for free.” Agree with him or not (and many certainly don’t), the development of individual value systems is crucial if we’re to begin sorting out the do’s and don’ts, yeses and noes of the Metaverse we want to see.

And then we need to put our time, attention, and economic weight behind projects which share our values, propping them up upon pedestals for all arriving developers to see. As we poke around the Metaverse for defects, we have to plug holes, apply salves, and drain all the poisons we know are there but which we can’t yet see.

There’s an enormous public out there awaiting anxiously, albeit unknowingly, the Metaverse’s proper arrival. Among them, an enormous contingent of future Metaverse artists, creatives who will emerge into the world one day and find in the Metaverse their best opportunity to express themselves and achieve success doing it. We can right now start building the scaffolding needed to guarantee that future.

I’d love to end this article with a comprehensive and exact list of things that need addressing, and sure, I have a few ideas, but they’re all mostly based on conjecture, prophecy, hearsay.

Thankfully, others have already formulated some solid ideas, like Metaverse developer Jin (@dankvr ), who knows far more about this technology, and where it may be headed, than I do. Jin tweeted out a list of characteristics any Metaverse would need to be truly “open.” I wanted to post it here in its entirety:

While these all seem to be reasonable, realistic goals to set for ourselves, actually achieving them will undoubtedly require mass coordination, experimentation, and effort.

It will require users.

A lot of them.

Let’s think of ourselves as cultural beta-testers, not here to see whether the technology works, but how the technology affects us and the culture around us. Can we have virtual auction-houses, I wonder, and can those auction-houses be truly decentralized? Can we arrange Metaverse worlds in a community-prioritizing way? What does web3 look like when applied en masse to real estate and architecture and life design?

And perhaps most importantly of all: If the Metaverse offers a further amputation between our “real” and “digital” lives, do we have the psychological and ethical infrastructures in place — personally and socioculturally — to help us integrate these alternating realities? Or will this further fragmentation simply compound the mental anxieties, angsts, and agonies which seem standard-order in this new, omnipresently-online age?

My friend, I wish I had the answers. I wish I knew the way forward. I wish this was a trail already blazed, but it isn’t. It’s our responsibility to blaze it. Through waist-deep water and frozen nights, machete-ing through brush and picking leeches off our skin one by squishy one.

And maybe, in forty years, when VR is integrated into every name-brand contact lens, when full-body tracking suits are sold at Primark, when physical sex is used to “add some spice into the relationship” (God, what dystopia have I imagined?), the safeguards, checks, and balances we design in the coming days may still be used, honored, and appreciated.

I mean, being on the ground floor of crypto art was probably cool, sure, but forget that; we could be on the ground floor of something galactic.

So let’s get on our spacesuits and go for a spacewalk. Before the universe collapses in on itself. Before this vast universe of possibilities is taken away from us, and all because we weren’t paying attention, because we couldn’t dare conceive of ourselves as pioneers.