Julian Brangold Sits Down with the Argentine 3D Artist

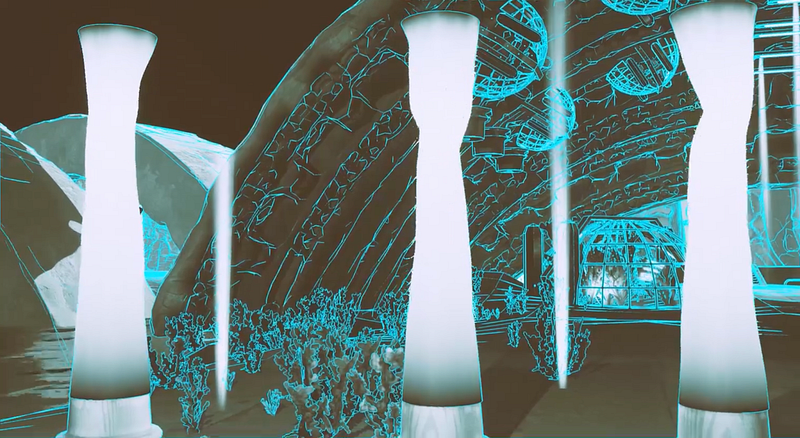

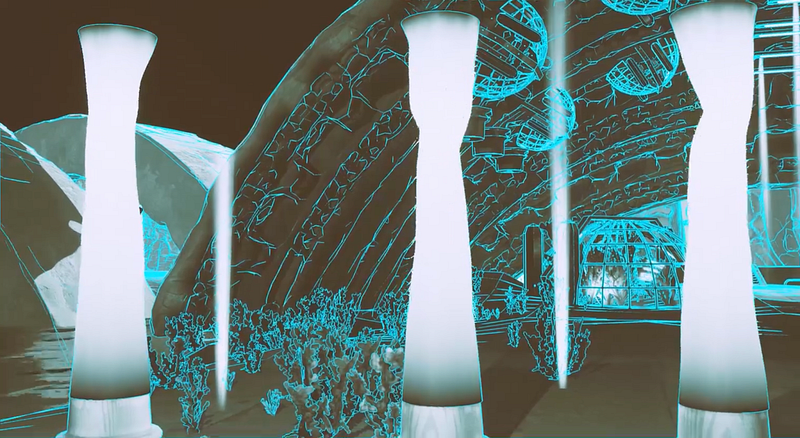

Deep beneath the surface of metal and silicone is a place where novel organic beings are being born, creatures that, much like totems, represent different states and forms of consciousness; they inhabit a world of creation and serve as guides or shamans that facilitate the navigation of digital reality. Right there beside them lies a spiritual force of world-making: a contemplative oasis made of many other oases. This for me is Joaquina Salgado’s work. A means of transportation to different realities, a place that creates places, all within a vast exploration of technology both clashing and fusing with biology.

Her work of survey into the medium of simulation (artwork in the form of real-time software that creates audiovisual experiences) looks at planes of being and explores space-time in a way that seeks to transpose the viewer’s state of mind. Both spiritual as well as playful, her research based practice has given shape to a reconnaissance-like array of different expressive media: still image, video and real-time simulation, as she explores the experimental use of video-game engines, 3D sculpting and modeling, animation and filmmaking.

The following a transcription and translation of a conversation between Joaquina Salgado and artist Julian Brangold recorded over Discord in May, 2022. This is part 1 of 2.

Julian Brangold: I tend to like to start with this question: When do you consider to have done your first work of art?

Joaquina Salgado: I think my first work of art was my college thesis, where I studied multimedia design, and I created a virtual reality experience in 2017, in which you’d enter the world of a medicine woman from a community of Argentinian native people, and you had some kind of conversation with plants. So that was the project, my first work was, taking that into account, to generate a sort of test, and beyond the technical exploration, I could also give it a justification and a meaning to what I was doing with Unreal Engine.

JB: What was your relationship with this tool before making this first project?

JS: As I worked on the thesis through a year-and-a-half, I was also learning Unreal Engine while making it. I hadn’t used it before. I might have used it a little bit, for developing some small scenarios.

But this time it was more about diving into programming and suddenly trying to combine the poetic world I had built with this language, blueprints and everything, it was really my first experience.

So all at once I had a huge new perspective open up for me. This work was even distributed through some festivals. That was when they started calling me an “artist”, before I even called that myself. So I did study design, but I gave everything a pretty poetic twist, and because I was named that way, I could start producing with that notion in mind, the use of the tool with a more subtle discourse.

JB: So your beginning to study this tool was because of the idea of creating a virtual experience.

JS: Yes, exactly, I had worked a lot with 3D before, in the show business mainly, I made some visuals every once in a while, but that was the first time I dove into Unreal and at the same time I deepened in a process. Everything happened simultaneously, and that was when I said, “This is my thing.”

JB: What about the works that came later on? Was it from this place of, “This is a work of art and now I’m an artist?” Or was it more like, “What other thing can I do with this tool?”

JS: I think from then on I started to dig a little more into the rendering world, not only as a product, but also as a picture-piece, it led me to it. Even though I was working on 3D mediums, maybe I was working more for commercial projects. That’s the reason I started to consider myself as a cultural agent, since other than the designer, I could give a meaning to the images I was producing, and then to my thesis piece, called Lawentuchefe.

JB: Tell me more about that name.

JS: It’s actually the name given to women dedicated to medicine in the Mapuche [indigenous inhabitants of Chile and Argentine] community. They’re also hierarchically leaders and counselors, that’s kind of their role. So they enter these parallel dimensions where they communicate with plants, and these plants tell them when they are ready to be harvested and turned into medicine. I wanted to represent this whole world, I even had several interviews. I traveled south near Bariloche to a community, I spent some time close to them,and this came out of it. Then I received a call from Mutek Festival, they asked me for a new piece that involved VR. And it was hard for me to consider myself an artist still, I didn’t think I was up for it. So I feel that as I was entering Mutek and this world of digital art festivals and electronic music, I could feel part of an artist community and realize it was a job like any other; yes, I think I felt there was something about the artist’s ingenuity I had to leave aside to consider myself as a part of that circuit.

JB: What did you end up doing for Mutek?

JS: That was called Fluido.vj. I made that one in 2019, and it was able to tour around quite a lot, appearing in many Mutek editions, in Canada, in Buenos Aires, in a festival in France, it was quite well-received. It later appeared in several festivals here in Buenos Aires as well. The work was more about an underwater journey, my visual universe is always related to the water element and the color blue, the world of emotions, maybe from a more abstract/poetic point of view. So what happened was you’d go through different landscapes of emotions, there’s a 360º documentation of it on YouTube. The idea is: There’s this loop you’d walk through, but at the same time you had a control panel with which you could control the lighting of the environment. This is linked to my vj’ing [real-time visual performance] practice: the lights, the screen working in tandem with the sound artists, the experience of looking into a place. How you can feel in a place that isn’t where you physically are. So mixing up these two things, as well as understanding that when you are vj’ing, controlling lights or screens, what you’re doing is guiding the mood of the people, along with the music, as if something happened in the mental and emotional levels that’s also related to color; that’s what I wanted to achieve with that work.

So as you were walking through different landscapes, you found a beach with these huge heads that were crying. Then you entered an electric tunnel and as you exited there was a scenery full of psychedelic mushrooms. You also played with the lights there. That was the most circulated VR work I made, my trampoline into interactive arts.

The first one was a pretty good rehearsal, but this one was something else, and I was able to insert it in a digital and interactive art circuit, and thanks to that I got connections with lots of institutions, artists and curators. This work was the one that got the most repercussions up to now out of all my artworks.

JB: Who came up with the idea of using VR in the first place? You? Or Mutek?

JS: At that moment I felt I was a “VR Artist”. Then I understood my practices weren’t linked to just one tool. At these exhibits there were always rooms with headsets and people using them. That year, Muteks’ organization was focusing on virtual reality works, and it turned out to be perfect for me to develop it with that format. Moreover, at that time, I was trying to take these imaginaries to an artificial environment, to generate the feeling of being there, not visiting a place, not a place you’ve seen before, but a place you’ve visited, that was my intention, and the VR format was perfect for it. So it was a stage, one of my first hard production stages.

JB: I see two great pillars in your work: one being the practice of world-making and environments. The other pillar is a bit more realistic, a sort of fiction that is in some way related to the physical world, but it has a fictional or fantasy twist.

JS: Yes, absolutely, aquatic fantasy.

JB: What is the relationship between water and your work?

JS: I don’t know… I’ve always been a fish, I’ve trained competitive swimming for years. There’s also something about the magical world, also astrological, if you see my astral map, literally everything is water. I liken it to the world of emotion, and I think my work has helped me bring out that side of me. There’s something about this element that just fascinates me: that it doesn’t have a shape, and it adapts according to its context as well as changing its state, from one thing to another. So I suddenly feel that my practice, where I explore different formats, different tools, different technologies, it doesn’t have such a defined form, and I think that was my clash as I entered the NFT world, because what I was working on didn’t have such a big field, its subject being more digital image and animation. So going back to the water element, which adapts its shape and takes the shape of its container, it provokes something in me and it’s something I think about on a sensitive level as I’m developing a discourse, it’s always present.

JB: When I see documentation on your installations, there’s something about the environment being controlled for the experience to be a certain way, that also contributes to the making of this world and the experience of that world. So how is your relationship with exhibition devices?

JS: There are some works with which I’m completely satisfied, for example the one I showed in Chela (No existe tierra mas alla by Cryptoarg), which was an environment where you’re a fish, so you’re an aquatic creature that goes around this space, and in these experiences I try to induce a calm state, as if it were some form of meditation, a digital meditation. I think that’s where the exploration tries to go, so in Fluido which also deals with water, you’ll see it’s more or less the same thing. Even though I think what I’m working on now is better visually — at least I like it better — I’m also trying to create a specific emotion in people as they go through it, related to calmness. A relaxed state, like when you’re sitting just looking at the sea, the horizon; pleasant and calm feelings, with a lowered stimulation or excitement. Those are the feelings I look for with my works, and I feel a world you can explore is a good way to transmit that. After that, some pieces can come out of it, like animations or other kinds of formats.

JB: In some way the creation of the world has a function. It exists to generate a certain state.

JS: Exactly, to generate a state. It’s a search that touches sound and color. Getting someone to a state, or trying at least, I mean I put in the intention, then each one lives it its own way. But yes, “to induce a state” could be a good way of describing it.

JB: Do you practice meditation?

JS: Yes, every day. I’m mostly doing some guided meditations, also Yoga Nidra, that’s a type of meditation where you go through your whole body and you take your mind to places or images that are linked to your subconscious, which then help you loosen something or work on something. More than anything, through meditations that make the subconscious visible to your consciousness, I gather lots of data for what I do. I’ve always had an approach to spirituality, but above all, since the pandemic, I’ve started studying it even more and I found a place that was related to my artistic practice, and I loved that, suddenly it’s a kind of channeling.

JB: In your thesis you had a research period of going to a place in-situ, investigating the theme, doing fieldwork. Is this a method you apply in general, where you have a period of research before you begin the actual execution of the work? Or do those things happen in parallel?

JS: I always try to have an idea before executing. In this particular case, yes, there was a lot of research, but also because the university format required that, the making of an essay, and there’s also something about the westernization of spiritual knowledge that makes the whole discourse be washed away. So what I do always starts with a previous research, finding a way to channel these ideas through super advanced technological tools, I don’t know, now I’m pretty into Mocap data for example. I’m now exhibiting an installation at Andreani Foundation called “Hidrontes”, and the research there started with a story by Donna Haraway called Los niños de Camille, [Children of Compost] which are basically post-apocalyptic societies where children are born and their souls are linked to an animal or a species they have to take care of. So suddenly a butterfly boy is born, and he has wings, so he’ll take care of the butterflies, and so on. From that idea, together with Nina Corti, aka “Qoa”, who was the person with which I made this installation, we put together the physical space, the natural and artificial elements that appeared in different places in the exhibition space, but always with a clear idea in mind. Sometimes I do just run some tests, and try techniques and that’s it; but usually everything I put up for exhibitions or mint has at least some conceptual background before the technical resolution.

JB: I generally like to think of artistic practice related to technology from the subversion of the tool, always giving it an unexpected twist so something out of the ordinary can come out of it. And I feel that Unreal Engine, since it’s an engine thought for high definition and high-end video games, I think with your work you’ve subverted the tool to create something that creates a displacement, where the experience and those things in the plane of the subtle are somewhere else, somewhere that has nothing to do with the complete optimization of the tool.

JS: Yes, absolutely; there’s always a play with the technical borders, and I think it’s just like you said, it’s part of the practice of art and media, even more if one doesn’t have a programming toolset. So suddenly, I don’t know how to use the tool for the making of a more sensible discourse. For me, not knowing is a very important part of the process.

JB: How much attention do you pay to the quality, or the visual correctness of the image? Are you interested in showing polished work? Or are you also interested in evidencing the device that exists behind?

JS: I think I emphasize the finish of little things, such as lighting and reflections and textures, mostly textures and materials; I pay a lot of attention to that. But I think very thoroughly on what I’m using as a part of the enunciation behind the works. Sometimes I do some things, mostly with images that I see are not symmetrical, there’s no harmony at the composition level. But when I take that to the stage of materials and lighting, that’s where I think I emphasize the finish, mostly to create this fantastical effect, that has something nice and stereotypical. But that doesn’t bother me, I don’t know exactly what to answer, it doesn’t bother me that that is seen, to be known that it was made with Unreal Engine; as a matter of fact, I like it, I suddenly feel like there are not many projects like this, with this kind of approach to the game engine.

JB: Are you interested in narrative?

JS: I think I’m a more loop person, you may say, like a cycle person; there may be a narrative but it’s pretty basic. Andreani’s work is a 5 minute looped animation. The work I showed in Chela wasn’t narrative, just an existing being, but everything was looped, the scenery was looped, the music was looped. There may be different stages, but not a narrative development like in movies, where there’s a dramatic point, and ending; maybe it’s just different stages that vary, where the ending is always connected to the beginning, like life.

JB: What are you working on now?

JS: Now, I’m about to launch a series that got delayed a little bit, because I wanted to finish some details, I didn’t want to hurry it. It’s a series that’s not related to the previous stuff, because I’m trying new things, but the plot here is when you go to a party that you think is going to be amazing, and suddenly, it becomes your worst nightmare, it’s a little bit like that. It’s a series with three images, although there may be more. There I put together some photoscan techniques, and then Zbrush and Cinema 4D, the images are a lot better than what can be achieved with Unreal Engine, more realistic.

I’m working on that on one side, and on the other I’m working on a project with Mocap data, in fact, with a Hindu choreographer who streams for me for a while and I put that into Unreal Engine, in time, through the internet. The idea is, since she also has a very spiritual exploration, we’re making a representation of Kali, who is one of the most important Hindu goddesses, a very strong feminine representation because she is the goddess of war and destruction. She doesn’t have a head, she cuts her own head off and she holds it in her hand, it’s like the goddess’ Phoenix, and at the same time she has a super masculine and warrior-like energy, while being a woman. So I’m doing this representation, and this dancer and choreographer will be Kali in this environment, we’re working on that together. These projects always take a lot of time. I’ve been working on it for four months now, and it will probably be ready by the end of the year.

So yes, that’s the main thing at the artistic process level. Then I would like to find a way to link it with the blockchain world because I think that would be very interesting. But for now that is in complete development.

These projects may take months to develop, and I sometimes feel they are behind the rhythms this crypto world proposes.

I feel that in the beginning I let myself create connections constantly, being there, staying; and now I find myself at a point where I say, “I’m going to work on this and I’m going to share it whenever I feel ready to and let it be what it has to be.”

I also feel I’m at a point where I make my own production rules in the crypto world, which doesn’t really have some defined rules, the only things one can see are certain aesthetics or tendencies that may look like success recipes, even though it’s not like that as much anymore. And I feel at this moment I’m trying to find my own rhythm and my own way of being able to express everything in this sensitive world about emotions and spirituality, again, in a super high-tech and fast environment. That’s kind of my search on the technical level as well as the conceptual one.